Why too many bedrooms is a problem for housing supply - Ray White

Contact

Why too many bedrooms is a problem for housing supply - Ray White

According to Nerida Conisbee of Ray White Group Chief Economist, there are around 13 million spare bedrooms across the country.

Last year we took a close look at the number of spare bedrooms in Australia. Based on research done by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, we found that there are around 13 million spare bedrooms across the country. This week we take a look at why it is important in solving the problems of housing supply, who has the most spare bedrooms and where it is likely that a shortage of higher densities may start to become a problem

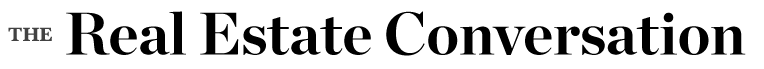

Australia has a lot of spare bedrooms with close to half of all households having more than two bedrooms spare. The calculation of how many spare bedrooms a household has is calculated based on the Canadian National Housing Standard. Broadly speaking, the standard sets out that no more than two people in a household should share a bedroom and single people over 18 years should have their own bedroom.

Overwhelmingly, couples without children have the most space with more than three quarters of them with two or more spare bedrooms. This is followed by lone person households with more than half of them having two or more bedrooms. The type of occupant is also interesting. People that own their own home are the most likely to have two or more spare bedrooms. Renters are the least likely.

While the analysis doesn’t specify the age of people living in the household, the analysis by ownership and family type suggests that it is older couples who own their own homes that have the most spare bedrooms. A third of couples without children have three or more spare bedrooms, clearly more than enough for most people’s requirements.

A lot of Australia’s housing problems aren’t necessarily about there being not enough homes but an inability to use these homes most efficiently. We like having a lot of extra space in our homes.

This became even more apparent during the pandemic. Even though international migration stopped during this time, rents rose, something that was difficult to explain at the time. Subsequent analysis by the RBA found that it was driven by more people choosing to live on their own and/or moving out of bigger households. The number of lone person households rose to its highest level recorded and average household size dropped to its lowest level, driven by rising wealth levels.

Downsizing is hard for people as they age. Emotionally, it is hard to move out of home where you may have raised a family, spent a lot of time and energy renovating/improving or been in for decades. Financially, it doesn’t really make sense. The family home is a tax free asset and investing in other things is not. Changes to superannuation legislation has changed this somewhat but is unlikely to be enough of a driver for some.

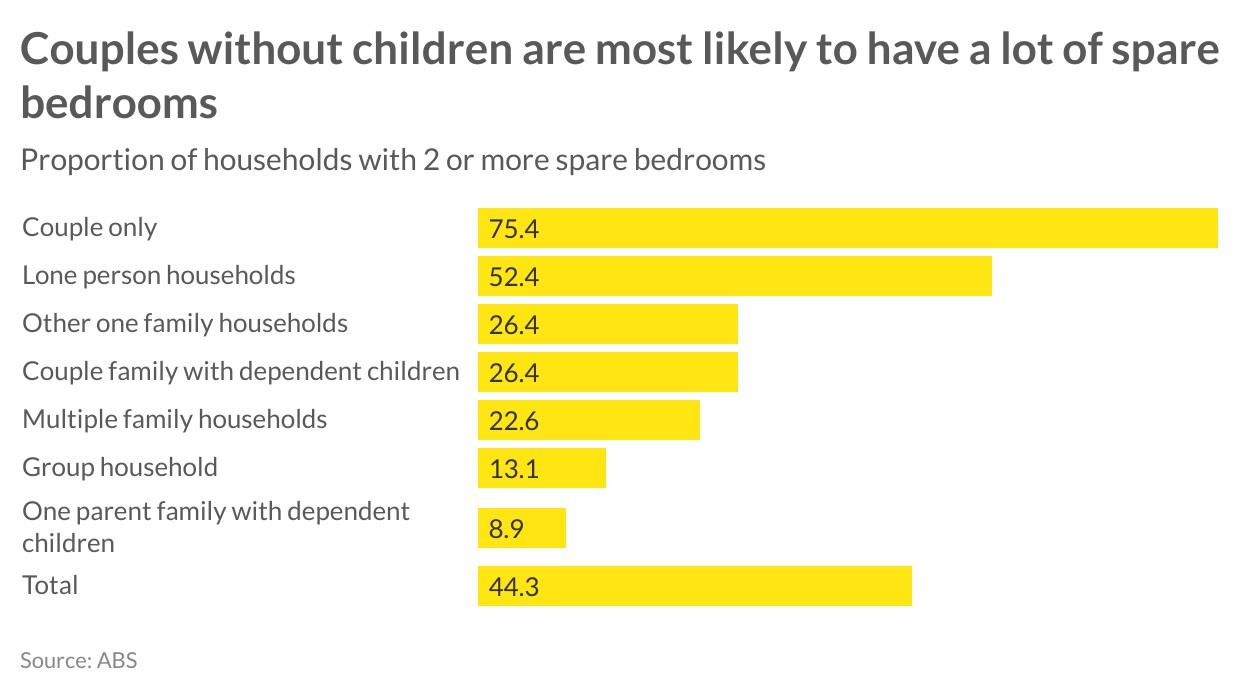

Fundamentally however, people like to age in the same suburbs they have spent a lot of their adult life. It is very rare for these suburbs to have suitable homes to downsize to. Building higher densities doesn’t just give younger people the ability to live in our most livable suburbs, it also allows older people to stay in them much longer.

By taking a look at the suburbs that have the highest proportion of people aged between 60 and 74 years, we get some sense where there potentially needs to be a greater supply of higher densities suitable for ageing residents. Many of the suburbs do contain higher densities however some are notable for having a lot of big family homes. By developing more suitable accommodation in places like West Lakes in Adelaide and Brighton in Melbourne, we could free up larger homes that can accommodate families that would better utilise all those bedrooms.